Plan Condor- What was it? And the Phases of Plan Condor

- John Zek

- Apr 23, 2025

- 6 min read

"A terrorist is not just someone with a gun or a bomb, but also someone who spreads ideas that are contrary to Western and Christian civilization."

- 1976 General Jorge Rafael Videla, former President of Argentina 1976-1981.

Santiago, Chile. November 25th, 1975.

It was a beautiful November day when the cars of the intelligence heads began to arrive. The headquarters of the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional that many called DINA, was an imposing colonial house and the central nerve of the fearsome Chilean secret police. Manuel Contreras was the head, a stocky figure with a grey steak in his slick combed hair and he stood watching the arrival of the motorcade. Contreras was in a good mood, for one thing, it was President Pinochet’s birthday today and he knew later there would be festivities at the Presidential Palace. The other reason was the meeting. After 1973 the ‘security situation’ in Chile had become stable as the military had wiped out the subversive terrorists. The problem now was many Marxists had fled the country and were continuing to use their power to foment a revolution- this meeting was a final solution to the problem.

As he stood at the window Contreras pondered the Americans. They confused him. On one hand the U.S secretary of state Henry Kissinger made public comments about his concerns of the security situation which Chile faced, but on the other hand his CIA connection told him to slow down DINA’s activities. He rubbed his chin. The CIA might think they understand the situation and that a few dollars could make him a traitor to the country, but he knew what this country needed, these subversives had to be eradicated.

As the intelligence heads filed into the meeting room cigars, whiskey and small cakes were passed around. The room filled with the lilt of Uruguayan and Argentinian accents and the smoke of the cigars. The meeting took a little longer than usual. The Argentinian delegate took a long time explaining the issues in Buenos Aires with an imperious air; most of the Marxists had converged there and the problem was not being fixed by President Isabel. There was a hint that the military was planning something soon. The Bolivians had pressed for more information about Peru and Brazil. The Paraguayans seemed more concerned with expelling Marxists from their country rather than hunting exiles.

They did it though, they agreed on co-ordinating intelligence on the subversives. They agreed their police forces could travel to another country and abduct them; they agreed that in Argentina they would finish what they had started and rid the continent of Marxist scum. They had American backing, in Panama the American base was the most sophisticated computer system in the entire world.

The Uruguayan delegation proposed to name the plan in honour of Chile and Pinochet. They suggested calling it Condor, the Chilean bird of prey; like the powerful Condor they too were hunting down rats that plagued their continent. And they would find them all.

Condor had begun

Plan Condor: What was it?

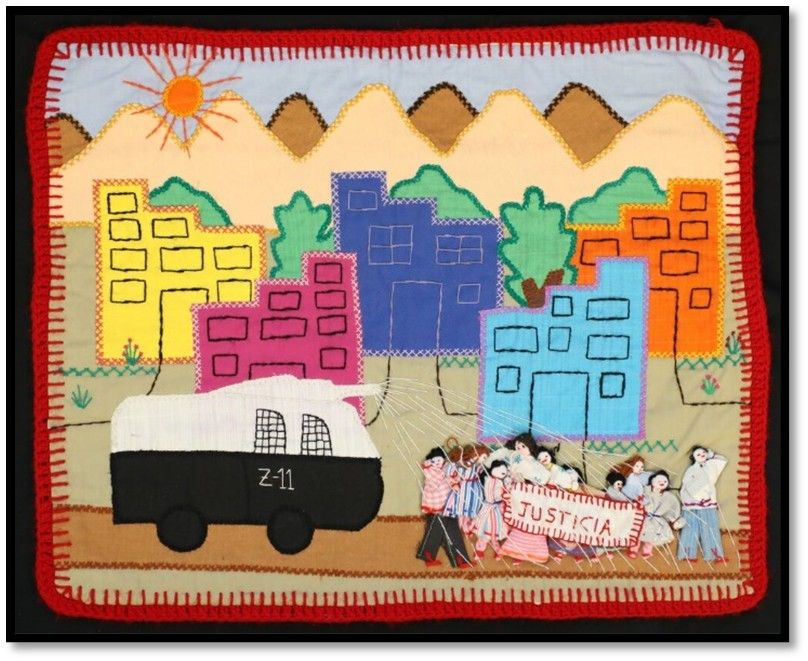

Following successive coups and military takeovers in Latin America from the early 1970s these regimes worked to eradicate militant and civilian political opposition commonly referred to as the Dirty War[i] (Spanish: Guerra sucia).

Argentina was the site of the worst excesses of the Dirty War largely due to the historical context. Earlier in the century Argentina had been a safe haven for radicals such as socialists and anarchists and so many exiled Uruguayans, Paraguayans, Chileans and Brazilians fled to Argentina. As the last country to fall to dictatorship it allowed all Condor nations to act with impunity to abduct and eliminate their political opponents found there.

Plan Condor (also known as Operation Condor and Condor[ii]) was one aspect of the Dirty War and a conspiratorial agreement between secret police agencies assisted by Western governments which allowed them to operate across the continent in a campaign of surveillance, abduction, torture, and assassination against perceived ‘enemies of the state’. Eight South American military Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Bolivia co-ordinated police agencies to create a supranational organization designed to enforce state terror, as General Francisco Brites, Chief of the Paraguayan National Police put it, Condor was

“something similar to what Interpol has in Paris, but devoted to subversion.”[iii]

Brazil joined this co-ordinated program several years after it was formally created, while Peru and Ecuador took part in information sharing and surveillance. Both the United States and France provided support to Condor nations by providing training on torture, access to communication networks and intelligence sharing. [iv]

“A global anti-Marxist agreement” -Michael Townley an American-born DINA assassin describing Condor at an Italian court in 1995. |

Condor supposedly aimed to “combat terrorism and subversion”[v] but as one U.S ambassador noted

“subversion- never the most precise of terms. One reporter writes that subversion ‘has grown to include nearly anyone who opposes government policy’”. [vi]

The reality was students, trade unionists, journalists, family, and any citizens suspected of being left-wing activists were targets by Condor, and they faced abduction which often meant torture and murder. Condor ‘officially’ started in 1975 when intelligence leaders from all the countries secretly met in the Chilean capital of Santiago but actual practices of Condor are recorded as early as 1969 when Brazilian political refugees were targeted and killed in Uruguay, Argentina, and Chile.[vii]

The number who died from Condor operations is a fraction of the overall victims of the Dirty Wars, likely numbering only in the hundreds but its reach was wide and kill teams travelled to Europe and U.S to conduct state backed assassinations that targeted high profile targets.

The phases of Condor

The Dirty Wars were at their height in Latin America when the security chiefs met in Santiago November 1975 This meeting was the first formalised agreement between Condor nations regarding how they worked together in their ‘operations’ i.e. abductions, torture and assassinations. The meeting minutes were found decades later in Paraguay in the ‘Archives of Terror’, and they appear quite benign and ambiguous, less than three pages of short bullet points.

U.S. American journalist John Dinges who lived in Chile during the some of the most violent years in the 1970s and has written extensively on Plan Condor notes:

“Phases Two and Three of the new organization were ‘operations’ activities so secret that the word itself does not appear in the documents”.[viii]

Instead these minutes were a cover, the vague language makes it seem like an intelligence sharing mission.

Phase One The initial phase of Condor was the creation of a centralized database that Southern Cone States could access and use to communicate whereabouts of subversives. In a 1976 cable from the U.S-Paraguayan ambassador Robert White to Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, White relayed a conversation with General Alejandro Fretes Davalos, chief of staff of Paraguay's armed forces who told White that Condor States

"[kept] in touch with one another through a U.S. communications installation in the Panama Canal Zone which cover[ed] all of Latin America” [ix].

U.S assistance was crucial for Condor states to track their targets across the continent, as at the time setting up a computerized database was technologically infeasible for these states.

Phase Two This phase was the agreement to allow police agencies to conduct cross border operations.

Phase Three The last phase is the most infamous, as one U.S. Senate report described in 1979[x]:

“Phase three operations involves the formation of special teams from member countries assigned to travel anywhere in the world to non-member countries to carry out ‘sanctions’ including assassination—against condor enemies.”

This was the most secretive phase of Condor and one that would take decades to uncover the true story of who knew and assisted.

Sources

[i] The term often only applied to Argentina but in this book Dirty War/s will refer to any Southern Cone state action in this period.

[ii] Francesca Lessa, Operation Condor: The Terror in South America. video, 1 hour, 32 seconds. Posted Jun 10, 2022 by Letters and Politics https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mKqmOfIf9m8&ab_channel=LettersandPolitics.

[iii] Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales. n.d. "Plan Condor: An Illicit Association to Repress Opponents." Accessed June 26, 2024. https://www.cels.org.ar/especiales/plancondor/en/#una-asociacion-ilicita-para-reprimir-opositores.

[iv] Patrice McSherry Predatory States: Operation Condor and Covert War in Latin America. (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2005).1-4.

[v] Central Intelligence Agency. A Brief Look at Operation Condor. August 22, 1978. Accessed June 26, 2024. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB416/docs/780822cia.pdf 2.

[vi]Department of State, Report to Kissinger: "The Third World War and South America," August 3, 1976. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB125/condor05.pdf p3

[vii] While Peru didn’t take an active part in assassinations, they did allow agents to murder exiles in the capital Lima. Giles Tremlett. Operation Condor: the illegal state network that terrorised South America." The Guardian, September 3, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2020/sep/03/operation-condor-the-illegal-state-network-that-terrorised-south-america?fbclid=IwAR3wmYHph1iHAO_gKH03wEAGajBjbXgH1u7Grmawf1M1KR1gIWrfM4tpXYE

[viii] John Dinges. The Condor Years. New Press, 2012. P. 31

[ix] U.S. Department of State. Cable from U.S. Ambassador Robert White (Paraguay) to Secretary of State Cyrus Vance regarding Second Meeting with Chief of Staff re Letelier Case." October 20, 1978.. 1 page. http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/news/20010306/condor.pdf

[x] Senate Subcommittee on International Operations Report, "Report: Activities of Certain Foreign Intelligence Agencies in the United States," National Security Archive, January 18, 1979. P. 11 https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/document/22394-5-senate-subcommittee-international

Comments