Women and the art of resistance

- John Zek

- May 21, 2025

- 7 min read

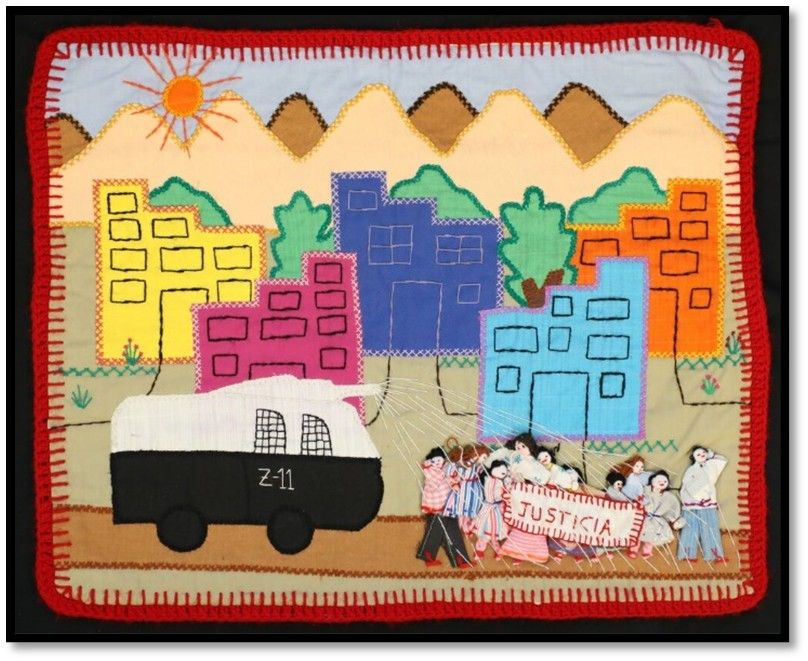

Above: Women Demand Justice!, n.d., Embroidered textile, 14 ¼ x 18 inches, Courtesy of Mario Avendaño [Photograph]. Arpilleras: Online resistance MOLAA.

Below: Aurora Ortiz. (Photo: Martin Melaugh) 'La cueca sola / Dancing cueca alone',(1st April 2016) Memorial da América Latina, São Paulo, Brasil

Paradoxically the brutal repression of regimes pushed women into new and different roles and to become more politically active as their husbands, brothers and sons were now absent, taken away from them. [i]

In Argentina and Chile women organised the most visible human rights groups such as the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo (henceforth The Mothers) and the Group of Family Members of the Detained Disappeared (AFDD). Both groups formed in response due to the lack of information or help from authorities towards the family members and friends.

In Chile the AFDD formed folklore and music groups, practicing dance and song as part of their protest, the Cueca Sola was one such dance developed there. The creation of arpilleras, traditional Chilean textile collages, which detailed many of the women’s struggle under the Pinochet regime were not only a form of protest but income. Western supporters could purchase the artworks providing much needed funds to the low-income neighbourhoods.

The Mothers in Argentina are one of the most recognizable organizations as they wore white shawls (meant to represent the nappies of their missing children) embroidered with the names of who they were looking for. They organised as early as April 1977 at the height of violence, meeting weekly at 3:30pm in the square opposite the Presidential palace. Husbands of the women were asked to stay at home, believing that men might provoke the police. María Adela Antokoletz remembers

"We endured pushing, insults, attacks by the army, our clothes were ripped, detentions. . . But the men, they would not have been able to stand such things without reacting, there would have been incidents they would have been arrested…most likely, we would not have seen them ever again.”[ii]

The military found the protests and call for public accountability such a threat to their rule that in December 14th, 1977, police conducted an operation which abducted and murdered 12 activists several of whom were the founders of The Mothers (see Alfredo Astiz). The unidentified bodies washed up on December 20th of that year after a storm and they were buried in mass grave. Despite the threat of death The Mothers were not deterred, “They thought there was only one Azucena [one of the founders], but there wasn't just one. There were hundreds of us," said member Aída de Suárez.

Alongside The Mothers emerged The Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo (The Grandmothers) that sought to find their missing grandchildren while other church and human rights groups documented and record the crimes of the Junta.

Children of the disappeared

Above Left to Right: Guillermo Perez Roisinblit,Anatole Larrabeiti, and Jorgelina Molina Planas

These are but some of the stories of the children of The Disappeared. They survived due to a twisted logic of the military, many of whom were Catholic. Left-wing parents were ‘sinners’ and could be slaughtered while newborn babies were free sin.

Over 500 children of the disappeared were abducted and often placed into the care of those cooperative with the Argentinian regime[iii]. Hundreds of these children have still not been identified, many of whom are by now middle-aged and human rights groups are still working to identify them.

Some were adopted by loving families who did not know the reason these children were orphaned; others adopted by the very jailors and torturers of their biological parents. The feelings can be complicated and conflicting, for Guillermo Perez Roisinblit, when he found out:

“I didn't see myself as their victim. In fact, it was the other way around. I thought that as the judicial investigation progressed, they[his adoptive parents] became my victims.”[iv]

Some children protect their ‘appropriators’ (a term used in Argentina for the adoptive parents) from legal action and maintain relationships with their adoptive parents, even after discovering the truth.

22 December 1976 in the Chilean port city of Valparaíso. Two young, well-dressed children step out of a black car with tinted windows in the town square. Locals watch as they wander the square alone, the local police are called but strangely no parents appear. Four-year-old Anatole Larrabeiti and his 18-month sister Victoria Eva ended up adopted together months later. What no one knew, was that these two children were in fact Uruguayan refugees who days before had been living in Argentina. Their parents, trade union activists, had been tracked and killed in a shootout[v]; the Argentinian police took the children to the Buenos Aires station for several days, then to the Uruguayan capital Montevideo and finally bizarrely they were flown to Chile and abandoned. He was taken in by a Chilean family and when he was seven Anatole’s adoptive family discovered that he and his sister were in fact children of the ‘disappeared’. His paternal grandmother had been tipped off by human rights organisations who had managed to track the children down. He and his sister remained in the care of their adopted Chilean family who ensured they kept ties with his biological family.[vi]

Sometime in the 1980s, Buenos Aires.

“I’ve always known I was adopted because I was almost four when my mum disappeared. But my adoptive parents told me that my parents were terrorists and had neglected me.”

Ana Molina sits in the hotel and writes to her granddaughter:

“Today is your ninth birthday, and even though I am in Argentina, your adoptive parents won’t let me see you. They say you belong to them …”

Years earlier, after the murder of two of her sons she had fled the country with her last remaining son and sought asylum in Sweden. In 1977, her daughter-in-law and granddaughter went missing. She began a search, in which she sent photographs to human rights organisations such as Amnesty International and the Grandmothers. Eventually a parishioner from the same church recognised the photos of her granddaughter Jorgelina. Despite knowing the location of her granddaughter, she was refused from seeing her: she had signed adoption papers fearing that if she refused, she may bring more police actions against her family. She began visiting Buenos Aires and found the school of Jorgelina, writing:

“We looked into each other’s eyes twice. Your adoptive mother was picking you up from school. I was overwhelmed by emotion. I wanted to run up and hug you, but I stood paralysed … It was so painful.”

Ana Molina never met Jorgelina. In 2010 many years after her death, Jorgelina received a suitcase from Sweden with all the letter her grandmother had written to her which had not been shown to her.

After the death of her adoptive mother Carolina reshaped her identity, changing from the name her adoptive parents had given her back to Jorgelina. When she did so her adoptive father disowned her. This shocked her, “It’s been hard because I felt he was a good man… He wouldn’t accept that I am Jorgelina”. She since has reunited with her biological family, a half-brother, and her maternal grandmother and practices art to recover from the trauma.[viii]

The Grandmothers and the hunt for the children of the disappeared.

“When I turned 80, I begged God not to let me die before I found my grandson”. - Estela Carlotto

Over three decades of work and the Grandmothers have found 133 missing children but believe there are up to 500 still missing. Those missing may potentially be living in many different countries now and approaching middle age while many of the Grandmothers are passing away.

Hope always dies last, Estela Carlotto one of the founding members of The Grandmothers had searched for her missing grandson since 1977 when her 22-year-old daughter Laura was taken by police and disappeared. Laura was three months pregnant; she was held in captivity until she gave birth. Her story was reconstructed based on information provided by various witnesses and a file she had with the Buenos Aires Police, Laura is said to have given birth handcuffed and was allowed only five hours with her baby before she was taken away. She was murdered months later, in a staged confrontation the police. [viii]With a name and an approximate birth date Estela Carlotto searched for decades, but information was scarce, and witnesses were silent:

“I…. had been travelling around the world looking for a baby, looking for a child, looking for a young man”.

A well-known public figure she recalled “Everybody kept asking me: ‘When is it going to be your turn?” and as the years ticked she worried she would never find him.

![Estela Carlotto hugs her grandson Ignacio Montoya Carlotto, son of her daughter Laura, she never stopped searching for him.LEO LA VALLE / Stringer (08 August, 2014) Estela de Carlotto, the president of Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo [Photograph]. Getty Images.](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/3161d7_afb9d34e647147cda6c8fd673318af2f~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_295,h_185,al_c,q_80,enc_avif,quality_auto/3161d7_afb9d34e647147cda6c8fd673318af2f~mv2.jpg)

Four years later the day came. On the 7th of August 2014, 36-year-old musician Ignacio Hurban, son of two retired farm workers was identified through DNA testing. For many in Argentina this was the healing moment of a nation’s psyche, in a later interview Ignacio said how people in the street approached him and cried on his shoulder. Despite the discovery of such shocking crimes against his parents Ignacio shows little resentment:

“It was horrible, to be ripped from your mother, but I have no recollection of that. Plus, what good would it do me to cry for what could have been? Or to start living a life of suffering that I have not lived? My parents suffered...

But I didn’t live through any of that. My memories are of growing up on the farm with a mother and a father. And they did everything any other parents would have done.”

For Estela:

“The only thought I had was: Laura can rest in peace now. I felt Laura said to me: ‘Mother, mission accomplished.’ But there’s so much still to do. I’m going to keep looking for the other missing ones.”[ix]

[i] Marjorie Agosin. The Dance of life: women and human rights in Chile. In: Brill, Alida. (ed) A Rising Public Voice: Women in Politics Worldwide. Feminist Press at CUNY, 1995. P. 233

[ii] Arditti, Rita. 1999. Searching for Life : The Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo and the Disappeared Children of Argentina. Berkeley: University Of California Press P. 35

[iii] Although not all families who adopted these children were sympathetic with the regimes or even knew that their child’s parents had been murdered. Juan Forero. “Argentina’s Dirty War Still Haunts Youngest Victims.” NPR, February 27, 2010. https://www.npr.org/transcripts/124125440.

[iv] Marcia De Los Santos. & Margarita Silva. 40-year Mystery: Australia May Hold the Key in Search for Argentina’s Stolen Children. SBS language. 7 February 2023. https://www.sbs.com.au/language/spanish/en/podcast-episode/40-year-mystery-roads-may-have-led-to-australia-for-argentinas-lost-children/1wxv8rtqh

[v] Sometimes this story was used as a pre-text to murder activists.

[vi]Giles Tremlett. Operation Condor: the illegal state network that terrorised South America." The Guardian, September 3, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2020/sep/03/operation-condor-the-illegal-state-network-that-terrorised-south-america?fbclid=IwAR3wmYHph1iHAO_gKH03wEAGajBjbXgH1u7Grmawf1M1KR1gIWrfM4tpXYE

[vii] Tone Sutterud. “I’m A Child of Argentina’s ‘Disappeared.’” The Guardian, September 20, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/dec/27/child-argentinas-disappeared-new-family-identity.

[viii] https://www.infobae.com/2014/08/05/1585564-la-historia-laura-la-madre-guido-carlotto/

[ix] Uki Goñi. A Grandmother’s 36-year Hunt for the Child Stolen by the Argentinian Junta. The Guardian, June 7, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jun/07/grandmothers-of-plaza-de-mayo-36-year-hunt-for-stolen-child

Comments